Don’t let the word ‘degrowth’ intimidate you because it’s definitely not about economic recession and deprivation of quality in our lives. Degrowth is a concept that has provoked environmentalists, social scientists, and economists long before it emerged as a major European intellectual movement in 2008 with the conference in Paris on “Economic De-Growth for Ecological Sustainability and Social Equity”.

As defined in the Journal of Cleaner Production, sustainable (aka environmentally and socially beneficial) degrowth is “an equitable downscaling of production and consumption that increases human well-being and enhances ecological conditions at the local and global level, in the short and long term”.

It’s therefore suggested that “human progress without economic growth is possible”.

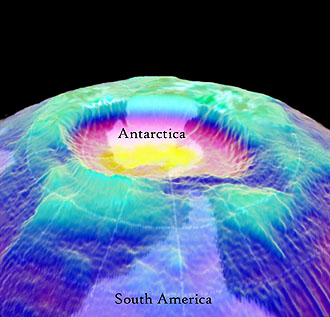

There are several alarm signs (vast energy and resource demand, uneven world wealth distribution, environmental disasters and rapid growth of the population) that call for the adoption of what the economist Herman Daly has been insisting on — the need for a steady-state economy which, as opposed to an indefinite economic growth, will be sustained by our ecosystem.

But what is really expected from a society that decides to renounce green capitalism and chooses to operate under sustainable degrowth instead? The prime idea is for people to lead a simpler life where they produce and consume less. Yet they are happier. As the Nobel prize winner psychologist Daniel Kahneman has found in his study with Angus Deaton, high income makes us think well of our lives (life evaluation) but it doesn’t necessarily make us happy (emotional well-being).

High income doesn’t necessarily make us happy

The repetitive pattern of commuting, producing, earning and spending bereave us of freedom to do the things we love, spend time with our family and friends and simply pause to think, feel sad or enjoy. A degrowth economy, therefore, is the spiritual alternative to what we know of a consumeristic and abundant modern life that harms our natural habitat.

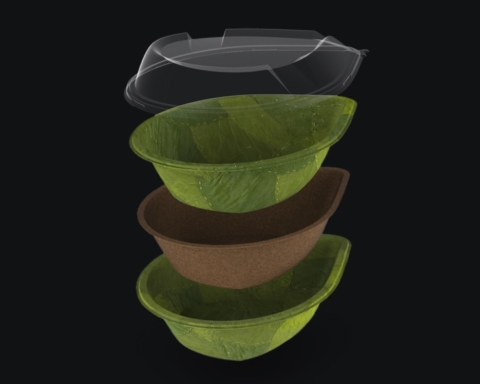

Eat locally farmed fruits and vegetables, live in energy-efficient homes armed with solar panels, wear recycled clothes and use the public transport to name but a few of the caring actions for a balanced relationship between natural and social welfare. So, the good news is that we have the solution to a lifestyle that will reverse the harm that Earth has been suffering.

The sooner we realize that the maniac consumerism is a one-way journey with not a happy ending, the more sense we will make of the degrowth economy — and the keener we will be to incorporate conscious changes in our day to day practices.